A recent report from Palo Alto Networks Unit 42 reveals the persistent and growing threat of DNS hijacking, a stealthy tactic cybercriminals use to redirect Internet traffic. Leveraging passive DNS analysis, the cybersecurity firm also provided real-world examples of recent DNS hijacking attacks – underscoring the importance of countering this hidden danger.

What is DNS Hijacking?

DNS hijacking involves modifying the responses of targeted DNS servers, redirecting users to attacker-controlled servers instead of the legitimate ones they intend to reach.

DNS hijacking can be done in several ways:

- Get control of the domain owner’s account, gives access to DNS server settings: In this scenario, the attacker has valid credentials with permission to directly change the DNS server configuration. The attacker may also have valid credentials for the domain registrar or DNS service provider and change the configuration.

- DNS cache poisoning: The attacker impersonates a DNS name server and spoofs a response, leading to attacker-controlled content instead of the legitimate one.

- Man-in-the-Middle attack: The attacker intercepts the user’s DNS queries and returns results that redirect the victim to the attacker-controlled content. This only works if the attacker has control over a system involved in the DNS query/response process.

- Change DNS related system files, as the hosts file in Microsoft Windows system. If the attacker has access to the local file, it is possible to redirect the user to attacker-controlled content.

Attackers typically use DNS hijacking to redirect users to phishing websites similar to the intended websites or to infect users with malware.

Detects DNS Hijacking with Passive DNS

The Unit 42 report described a method for detecting DNS hijacking via passive DNS analysis.

What is Passive DNS?

Passive DNS describes terabytes of historical DNS queries. In addition to the domain name and DNS record type, passive DNS records generally contain a “first seen” and a “last seen” timestamp. These records allow users to track the IP addresses that a domain has referred users to over time.

For a record to appear in passive DNS, it must be requested by a system whose DNS requests are recorded by passive DNS systems. This is why the most comprehensive passive DNS information generally comes from providers with high query volumes, such as ISPs or companies with large customer bases. Subscribing to a passive DNS provider is often advisable, as they collect more DNS queries than the average company, providing a more complete view than just local DNS queries.

SEE: Everything you need to know about the threat of malicious cyber security (TechRepublic Premium)

Detects DNS Hijacking

Palo Alto Networks’ approach to detecting DNS hijacking starts by identifying never-before-seen DNS records, as attackers often create new records to redirect users. Never-seen-before domain names are excluded from discovery because they lack sufficient historical information. Invalid entries are also removed in this step.

The DNS records are then analyzed using passive DNS and geolocation data based on 74 features. According to the report, “certain features compare the historical usage of the new IP address to the old IP address of the domain name in the new record.” The goal is to detect anomalies that may indicate a DNS hijack. A machine learning model then provides a probability score based on the analysis.

WHOIS records are also checked to prevent a domain from being re-registered, which generally results in a complete IP address change that can be detected as DNS hijacking.

Finally, active navigations are performed on the domains’ IP addresses and HTTPS certificates. Identical results indicate false positives and can therefore be excluded from DNS hijacking operations.

DNS hijack statistics

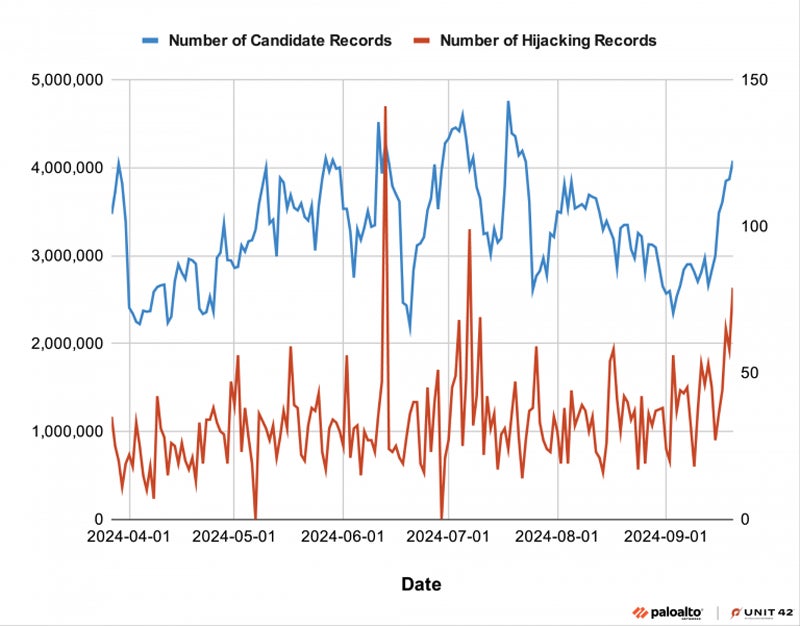

From March 27 to September 21, 2024, researchers processed 29 billion new records, of which 6,729 were flagged as DNS hijacking. This resulted in an average of 38 DNS hijacking records per day.

Device 42 indicates that cybercriminals have hijacked domains to host phishing content, deface websites, or spread illegal content.

DNS Hijacking: Real World Examples

Unit 42 has seen several cases of DNS hijacking in the wild, mostly for cybercrime purposes. Nevertheless, it is also possible to use DNS hijacking for cyber espionage.

Hungarian political party leads to phishing

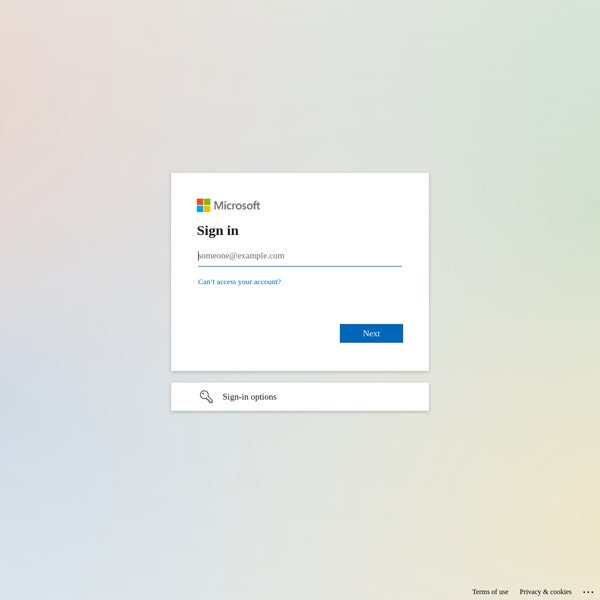

One of the main political opposition groups to the Hungarian government, the Democratic Coalition (DK), has been hosted on the same subnet of IP addresses in Slovakia since 2017. In January 2024, researchers detected a change on the DK website, which suddenly resolved a new German IP address, leading to a Microsoft login page instead of the political party’s usual news page.

American company destroyed

In May 2024, two domains were hijacked by a leading American management company. The FTP service, which has been leading to the same IP address since 2014, suddenly changed. The DNS nameserver was hijacked with the attacker-controlled ns1.csit-host.com.

According to the research, the attackers also used the same name servers to hijack other websites in 2017 and 2023. The goal of the operation was to display a compromised page from an activist group.

How companies can protect themselves against this threat

To protect against these threats, the report suggested that organizations:

- Implement multi-factor authentication to access their DNS registrar accounts. Establishing a whitelist of IP addresses that access DNS settings is also a good idea.

- Utilize a DNS registrar that supports DNSSEC. This protocol adds a layer of security by digitally signing DNS communications, making it more difficult for threat actors to intercept and falsify data.

- Use network tools that compare the results of DNS queries from third-party DNS servers—such as those from ISPs—with the results of DNS queries obtained when using your company’s standard DNS server. A mismatch may indicate a change in DNS settings, which could be a DNS hijacking attack.

Additionally, all hardware, such as routers, must have updated firmware, and all software must be updated and patched to avoid being compromised by common vulnerabilities.

Disclosure: I work for Trend Micro, but the opinions expressed in this article are my own.